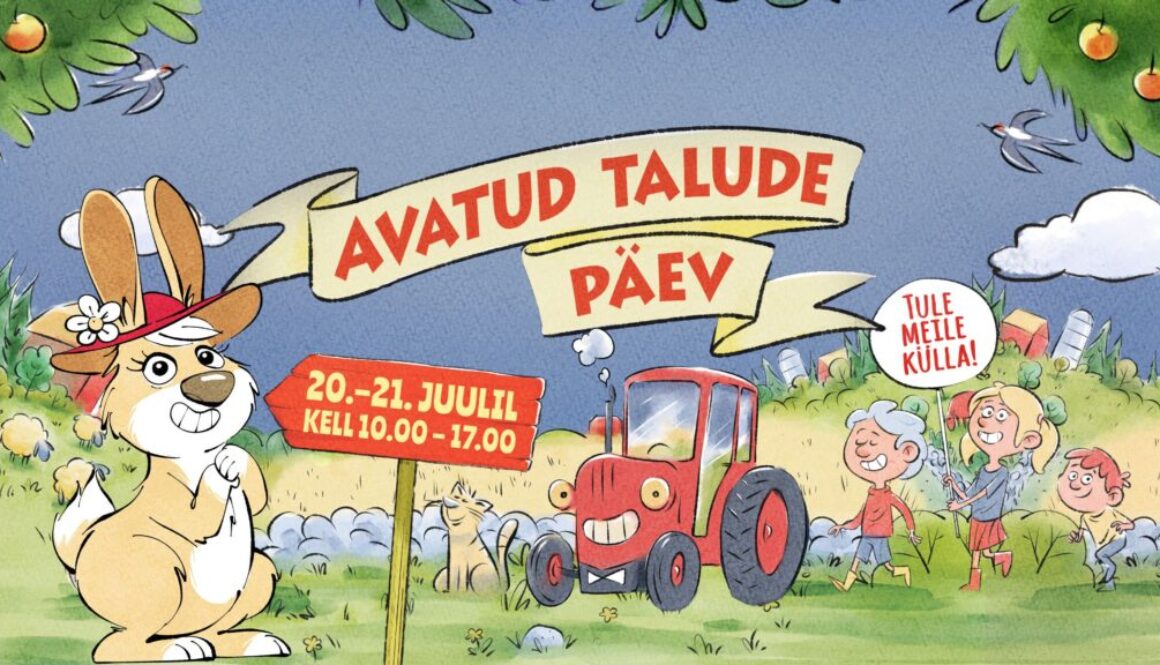

AVATUD TALUDE PÄEV 20. ja 21. juulil 2024 kell 10-17

https://www.avatudtalud.ee/kulastajale

Saun aitab tervist tugevdada, aga kuidas? ERR Novaator koos Vikerraadioga kogus kokku rea fakte, mida iga saunasõber võiks teada.

1. Saun treenib meie keha termoregulaatorit

Meie kehas on selline asi nagu termoregulatsiooni mehhanism. Põhimõtteliselt see aparaat, mida me hooldame karastamisega. Aga tänapäeva inimene on mugav: toas on kogu aeg soe, autos on soe, riided on ilmastikukindlad ja meie termoregulatsiooni aparaat teeb võimalikult vähe tööd. Aga siin tulebki mängu saun.

Kuuma ja jaheda vaheldumisega treenime oma termoregulatsiooni aparaati. Igapäevakeeles nimetame seda tegevust karastamiseks.

Regulaarne saunas käimine suurendab meie keha võimet panna vastu äärmuslikele temperatuuridele. Näiteks ootamatult külma või ootamatult palava kätte sattudes oskab karastatud keha nendega toime tulla.

2. Saun treenib südant ja veresooni

Saun mõjub hästi ka südamele, sest kuuma ja külma vaheldudes veresooned vaheldumisi ahenevad ja laienevad. See teeb veresooned vastupidavamaks ja treenib ka südamelihast, mis peab pumpama rohkem verd meie kehas.

3. Mikroobid surevad saunas

Kuumus tugevdab tervist ka selle kaudu, et tapab mikroobe meie naha pinnal ja kurgu ning nina limaskestadel. Meie naha pinna temperatuur võib saunas tõusta kuni 45 kraadini ning selle juures surevad sellel olevad mikroobid.

Hingates kuuma õhku sisse, surevad ka bakterid ja viirused, mis muidu kinnitaksid end meie nina- ja kurguepiteelile ehk limaskestadele ning tekitaksid seal põletikke. Nii on võimalik külmetushaiguste perioodil vältida ülemiste hingamisteede haigusi.

Samuti tapab kuumus ka saunalaval olevaid mikroobe, mistõttu ei tasu üldjuhul karta ka ühissaunadest mõne haiguse saamist.

4. Vihtlemine on massaaž ja vabanemine

Massaaž lõdvestab lihaseid, parandab vereringet ning vihtlemine ongi massaaž. Saunameister Priit Veeroja nendib, et lisaks mssaažile on saunaskäik ja vihtlemine ka meeli puhastav protseduur. See võimaldab vabaneda igapäevapingetest. “See on selline nullpunkt, kus saab igapäevarutiinidest vabaneda,” nendib Veeroaja.

5. Igal vihal on oma energia

Priit Veeroja sõnul on rahvapärimuse kohaselt erinevast materjalidest vihtadel on erinev energeetiline toime*. Värske viht, olgu ta näiteks kasest või tammest, annab saunaruumi oma aroomi ja tekitab selle kaudu meeleolu. Veeroja soovitab anda vihale vunki juurde näiteks lisades sinna n-ö hooajalisi taimi: mõni mustsõstra- või piparmündioks.

Saunaviha võib kokku panna ka 8-9 taimest, mis teeb viha eriti vägiseks.

Rahvatarkuse järgi on ka vahe sellel, millal viht on tehtud. Noore kuu ajal tehtud viht aitab kasvatada energiat, kahaneva kuu ajal tehtud vihaga saab endast aga midagi ära anda, näiteks mõnest halvast emotsioonist või harjumusest vabaneda.

6. Vihaga tuleb omamoodi toimetada

Kuivatatud viht tuleb enne vihtlemist saada taas pehmeks. Sageli panevad inimesed viha selleks kuuma või suisa keevasse vette. Aga looduses ei puutu taimed kokku nii kuuma temperatuuriga, mistõttu ei taha ka kuivatatud viht “ellu ärkamiseks” keevat vett.

Selle asemel tasuks viht panna viieks minutiks külma või toasooja vette ning panna tunniks-paariks kilekotti pehmenema. Kiiremaks lahenduseks on kallata vett läbi viha kerisele ning keriselt tulev aur teeb samuti viha pehmeks.

Kui vihtlemine tehtud, ei tasu vihta jätta vette, sest nii kaotab viht kõige kiiremini oma lehed.

7. Haigus tuleb sisse jalgadest ja läheb välja peast

Nii ütleb taas rahvatarkus, kuid vihtlemisel võiks seda teadmist kasutada nii, et alustada vihtlemist jalgadest ja liikuda mööda keha pea poole. Nii on Veeroja sõnul vere ja energia liikumine kehas kõige parem.

Sauna ja tervise teemal rääkisid Tartu Ülikooli ajakirjandustudengid teadlaste ja asjatundjatega Vikerraadio saates “Huvitaja”. Soovitame kuulata ka reportaaži otse saunast ning saunameistri nõuandeid vihtlemise osas:

https://otse.err.ee/media/embed/931276

*Saunameister Priit Veeroja on etnoloogidelt uurinud sauna kohta käivat rahvapärimust, et kasutada neid teadmisi saunaprotseduuridel ja vihtade tegemisel.

Allikas: Novaator.ee/tervis

Toimetaja: Marju Himma

A powerful documentary about the Baltic state’s sauna tradition has proved a surprise hit. But what’s it like for an outsider to join this sacred and intimate space?

“We are your sauna sisters now. Tell us what you’re afraid of.” The three women I have just met eye me expectantly. “Er, I wouldn’t say I’m afraid, exactly, more apprehensive about how hot the sauna will be, and how cold the water is …”

I’m at Mooska Farm in Võru county, south-east Estonia, to try a traditional smoke sauna. The earliest written records of Estonian saunas date from the 13th century, and the country’s smoke sauna culture was added to Unesco’s cultural heritage list in 2014 (many think of Finland as the home of sauna, but its sauna culture wasn’t listed until 2020.) This year, the smoke sauna has come to international prominence thanks to Smoke Sauna Sisterhood, an astonishing documentary that won a directing award at the Sundance festival and is Estonia’s entry for the Oscars.

The film appears to document the users of a single sauna over a year. In fact, filming took place at 10 saunas over seven years – and Mooska is one of them. It takes a little effort to reach it: I took a two-hour train ride from the capital, Tallinn, to Tartu, a university city and next year’s European capital of culture. There I met Elin, who is promoting Estonia’s “year of sauna”. We drove further south-east for an hour, then stopped in a forest to prepare physically and mentally. We collected drinking water from a spring, walked through a bog (Estonia’s most ancient landscape) and climbed the country’s highest hill, Vällamägi (a mighty 304 metres) for a few moments of mindfulness in a circle of trees.

Then it was onwards to Mooska, where I met Eda, the sauna master, and Kai, who would be helping. The four of us stripped naked and stepped outside. It was the last day of October, a few degrees above freezing, but with patches of snow on the ground. The swimming pond in front of me was frozen around the edges.

I had assumed we would warm up in the sauna before thinking about the pond, but no: we were going “swimming” first. “Don’t think about it, just do it!” commanded Eda. I took deep breaths and marched down the wooden steps into the icy depths, submerging myself to the neck for four breaths, then charged back up and straight into the sauna.

I lay on the top bench and instantly started to thaw out. I felt an incredible rush: elated and teary all at once. Eda closed the door and began to chant in her Võro dialect. The temperature rose as she threw water on the hot stones (to create steam – leil in Estonian) and started to beat a drum.

The sounds and sensations were otherworldly; part of me loved it, but another part wondered how long I could stand the raging heat. I had been told I could move to a lower level if I got too hot, and leave whenever I wanted, but a combination of self-consciousness and stubbornness kept me rooted to the spot.

Eventually, Eda said it was time to take a break. The sauna was in one half of a log cabin; the other room was pleasantly warmed by a central wood burner. We sat on rug-lined benches around the stove wrapped in blankets, drinking tea sweetened with honey. I learned what makes a smoke sauna unique: the wood in the oven is lit up to eight hours in advance; there is no chimney, so the room fills with smoke; the smoke is released before people enter, but the stones in the hearth remain hot.

We repeated the process several times over the next three hours: the ice-cold dip, the red-hot sauna, the tea and rest. Yet each sauna round was different: we rubbed ourselves with ash, then salt, and later honey, and washed it all away. We focused on our ancestors; on what we wanted to let go of and what we were thankful for; on times we had felt powerful. Eda instructed, chanted, rang bells, drummed, massaged our shoulders. At one point she told me to exhale like a coffee plunger, all the way down: “More, more, more!”

The climax of each sauna visit was the “whisking” with viht, dried bunches of leaves. Eda used them to lightly slap us all over, stimulating the skin and generating the most intense heat. Face-down in more of the leaves, I forced myself to breathe deeply, fighting a rising sense of panic. Finally, she encouraged us to let it all out by screaming. I sat up and managed a pathetic high-pitched shriek, while the others dropped to their knees and released deep, cathartic, guttural howls.

After my final plunge in the pond, I returned to the sauna and Kai told me to curl up “like a baby”. She tucked fragrant leaves around me and stroked them over my body. It was warm and dark and comforting, almost womb-like. I began to see why, in the film, the women tell such intimate, often traumatic, stories while they’re in the sauna. A sauna is a sacred space to Estonians – one where babies were once born, and the dead tended to – and, even to an outsider, it feels safe.

Afterwards we had dinner at Suur Muna, a cosy restaurant nearby where all ingredients are sourced from within 15km. It even serves traditional sauna-smoked pork, as seen in the film (these days it is smoked in a separate sauna). I find being in a sauna works up an appetite; I devoured my creamy chanterelles with purple potatoes, and sampled a sparkling rhubarb wine (divine) and a fermented birch juice (disgusting). I could barely keep my eyes open on the way back to Tartu and my room at Hotel Lydia, a 19th-century building in the old town.

There are about 400 smoke saunas in Estonia, mainly in the south-east, but they are not the only kind. There are 100,100 in total, for 1.3 million inhabitants, including Finnish saunas, electric saunas, raft saunas, barrel saunas and more.

For contrast, the next day I headed back to Tallinn’s hip seafront quarter of Noblessner, for an igloo sauna. This former submarine and shipbuilding district has been transformed over the past few years and now boasts Estonia’s only two-Michelin-starred restaurant, 180°, plus more casual dining (I had lunch at the excellent Lore Bistro), the Pohjala brewery taproom (complete with sauna!), the Kai Art Centre and lots of new apartments. It is also home to Iglupark, where groups can book a private igloo-shaped sauna (the Beckhams have one in their garden), with its own terrace and ladder down to the sea (from €50 an hour for up to 10 users, minimum three hours).

Most groups just hire the igloo, but I had my own sauna master, from Elamus Spa, the spa with the largest selection – 22 – of saunas in the Baltics. My session with Karl lasted about an hour, but still included many of the rituals – the scrubs, the musical instruments, the chanting, the whisking, even the yelling – and we finished with a plunge into the Baltic – and yes, it was. He also incorporated essential oils and shea butter, combining sauna and spa treatment.

It may not have had the intensity of Eda’s smoke sauna, but I still felt fantastic afterwards. Iglupark is more accessible for many, being close to the city centre and reasonably priced, and is one way of keeping the sauna tradition relevant to younger people. Even more affordable are the 41 remaining public saunas across the country, including six in Tallinn (about €6.50 for two hours).

I left Estonia wondering why Britain, another chilly northern European nation, doesn’t have its own sauna tradition. It may not get as cold as Estonia, but winter can be long, dark, wet and miserable. I learn that unheated Tooting Bec lido in south London has a sauna and is due to reopen after refurbishment. Bring it on! My sauna fear seems to have disappeared.

Perhaps I can ask Victoria Beckham if she wants to be my sauna sister …

The trip was provided by Visit Estonia. Guided saunas at Mooska Farm cost from €300 for three hours for up to eight people. Smoke Sauna Sisterhood is in selected cinemas now and will be available on demand from January