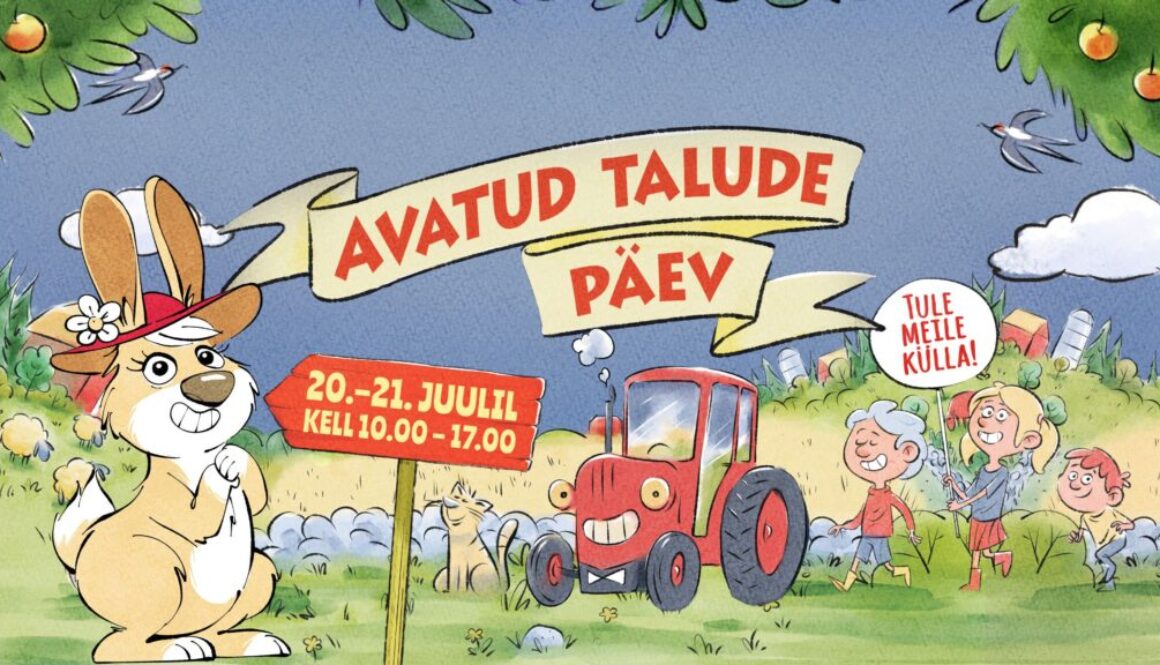

AVATUD TALUDE PÄEV 20. ja 21. juulil 2024 kell 10-17

https://www.avatudtalud.ee/kulastajale

When Hegert Leidsalu, of the Tartu City Government office, woke up on a cold and snowy Wednesday morning, he’d only expected to be doing a little driving. Sixty minutes later, I, a complete stranger, was massaging ash into his pert naked buttocks, as if basting him for the oven. Were we mortified? Most definitely. But at least we could blame our pinkening cheeks on the heat as we sweated politely inside a traditional smoke sauna in Haanja.

This tiny village falls under one of 19 municipalities in southern Estonia that join the city of Tartu in celebrating its European Capital of Culture title in 2024. Nor are they alone. This year, the accolade is also being shared with two other cities: Bad Ischl in Austria and Bodø in northern Norway.

Draw lines between these three places and you have an almost perfect triangle spanning the length and breadth of Europe. Thousands of kilometres separate them, and yet, often unknowingly, common threads and themes tie them together. For example, none of the cities have kept the title for themselves. Instead, they’ve all included the surrounding towns and villages in sharing the ripples of change that are often brought about by the interest that the celebrations typically bring. I spent three weeks visiting each one for their opening ceremony to see what lies in store for travellers, and what titles like this actually hope to achieve. If the aim of the European Commission grant is about seeing people and places in a new light, then basting Hegert’s bum had been an illuminating start.

One inarguable thread connecting these three destinations is their sauna culture. In the heart of the Austrian town of Bad Ischl, I found myself in the thermal spa Eurothermen, where I was joined by Marcus, a local man aiming to alleviate his arthritis.

“The sauna ceremony is deep in our culture,” he told me as a hefty gentleman swirled a towel around our heads, wafting blasts of hot air in our faces.

“Us Brits tend to err on the shy side of nudity,” I replied, flinching with the heat.

“No, no. You need to be completely naked to get everything out,” he rebuked, and I felt that there was a deeper meaning to his words, perhaps about the layers that we all wear.

Bad Ischl, south-east of Salzburg, is part of Austria’s Salzkammergut, a lake-studded ‘salt domain’ as seductive as anything in The Sound of Music. This spans the regions of Salzburg, Upper Austria and Steiermark, and was the private property of the Habsburgs for 650 years. Back then, nobody was allowed to enter or leave without a special permit or passport, and the dynasty used the nearby 7,000-year-old salt mine (the world’s oldest) at Hallstatt as their personal piggy bank. Because salt was the only means of preserving food back then, this ‘white gold’ lined the Habsburg coffers until their demise in 1918.

The family was impossibly rich but had been plagued by misfortune. Sophie, the wife of Archduke Franz Karl Joseph, had suffered several miscarriages. So, when the desperate Archduke was told by doctors looking after the miners that inhaling the region’s salts was healing, he sent his wife to bathe in its waters. Whether it had an effect or not, she gave birth to the first of four sons, Franz Joseph, in 1830. He was nicknamed the ‘Salt Prince’, and Bad Ischl’s spa reputation was born.

Franz Joseph and his wife, Elizabeth, also later took up regular summer residence in Bad Ischl, at the Kaiservilla. Their influence attracted the great musicians, composers and artists of the day, transforming a rural town into a flamboyant beauty and noted spa escape. It’s this history that the artist Simone Barlian drew on when building Plateau Blo, a floating sauna that will rove around Lake Traunsee – Austria’s deepest – during the year-long Capital of Culture celebrations.

“Lakes link the region, so I wanted both a physical and metaphorical platform where the public could share open dialogue,” she said while standing next to the pewter coloured water. “In a sauna, everyone is naked – the same. It’s an equaliser. And whether you’re the mayor or a citizen, you can come together and discuss the future.”

The idea of sauna as a meeting place had also been drilled into me at the UNESCO-listed smoke sauna that I’d shared with

Hegert in Estonia. There, on Mooska Farm, owner Eda Veeroja had told me: “In a sauna, the conscious world of understanding ends and the in-between world begins.” Immediately afterwards, she’d opened the door of the alder-wood cabin to reveal its innards, shadowed with soot, where I would be scrubbed with salt, ash and a gloop of local honey before being patted with birch branches.

“Here, it’s possible to come into contact with our ancestors and their wisdom,” Eda whispered. “They are a liminal space between the forest and the farmhouse – a place for healing, magic and communication. The country grannies and grandpas are bearers of these Indigenous ways of life.”

Read full article from Wanderlust April/May addition here.

Saun aitab tervist tugevdada, aga kuidas? ERR Novaator koos Vikerraadioga kogus kokku rea fakte, mida iga saunasõber võiks teada.

1. Saun treenib meie keha termoregulaatorit

Meie kehas on selline asi nagu termoregulatsiooni mehhanism. Põhimõtteliselt see aparaat, mida me hooldame karastamisega. Aga tänapäeva inimene on mugav: toas on kogu aeg soe, autos on soe, riided on ilmastikukindlad ja meie termoregulatsiooni aparaat teeb võimalikult vähe tööd. Aga siin tulebki mängu saun.

Kuuma ja jaheda vaheldumisega treenime oma termoregulatsiooni aparaati. Igapäevakeeles nimetame seda tegevust karastamiseks.

Regulaarne saunas käimine suurendab meie keha võimet panna vastu äärmuslikele temperatuuridele. Näiteks ootamatult külma või ootamatult palava kätte sattudes oskab karastatud keha nendega toime tulla.

2. Saun treenib südant ja veresooni

Saun mõjub hästi ka südamele, sest kuuma ja külma vaheldudes veresooned vaheldumisi ahenevad ja laienevad. See teeb veresooned vastupidavamaks ja treenib ka südamelihast, mis peab pumpama rohkem verd meie kehas.

3. Mikroobid surevad saunas

Kuumus tugevdab tervist ka selle kaudu, et tapab mikroobe meie naha pinnal ja kurgu ning nina limaskestadel. Meie naha pinna temperatuur võib saunas tõusta kuni 45 kraadini ning selle juures surevad sellel olevad mikroobid.

Hingates kuuma õhku sisse, surevad ka bakterid ja viirused, mis muidu kinnitaksid end meie nina- ja kurguepiteelile ehk limaskestadele ning tekitaksid seal põletikke. Nii on võimalik külmetushaiguste perioodil vältida ülemiste hingamisteede haigusi.

Samuti tapab kuumus ka saunalaval olevaid mikroobe, mistõttu ei tasu üldjuhul karta ka ühissaunadest mõne haiguse saamist.

4. Vihtlemine on massaaž ja vabanemine

Massaaž lõdvestab lihaseid, parandab vereringet ning vihtlemine ongi massaaž. Saunameister Priit Veeroja nendib, et lisaks mssaažile on saunaskäik ja vihtlemine ka meeli puhastav protseduur. See võimaldab vabaneda igapäevapingetest. “See on selline nullpunkt, kus saab igapäevarutiinidest vabaneda,” nendib Veeroaja.

5. Igal vihal on oma energia

Priit Veeroja sõnul on rahvapärimuse kohaselt erinevast materjalidest vihtadel on erinev energeetiline toime*. Värske viht, olgu ta näiteks kasest või tammest, annab saunaruumi oma aroomi ja tekitab selle kaudu meeleolu. Veeroja soovitab anda vihale vunki juurde näiteks lisades sinna n-ö hooajalisi taimi: mõni mustsõstra- või piparmündioks.

Saunaviha võib kokku panna ka 8-9 taimest, mis teeb viha eriti vägiseks.

Rahvatarkuse järgi on ka vahe sellel, millal viht on tehtud. Noore kuu ajal tehtud viht aitab kasvatada energiat, kahaneva kuu ajal tehtud vihaga saab endast aga midagi ära anda, näiteks mõnest halvast emotsioonist või harjumusest vabaneda.

6. Vihaga tuleb omamoodi toimetada

Kuivatatud viht tuleb enne vihtlemist saada taas pehmeks. Sageli panevad inimesed viha selleks kuuma või suisa keevasse vette. Aga looduses ei puutu taimed kokku nii kuuma temperatuuriga, mistõttu ei taha ka kuivatatud viht “ellu ärkamiseks” keevat vett.

Selle asemel tasuks viht panna viieks minutiks külma või toasooja vette ning panna tunniks-paariks kilekotti pehmenema. Kiiremaks lahenduseks on kallata vett läbi viha kerisele ning keriselt tulev aur teeb samuti viha pehmeks.

Kui vihtlemine tehtud, ei tasu vihta jätta vette, sest nii kaotab viht kõige kiiremini oma lehed.

7. Haigus tuleb sisse jalgadest ja läheb välja peast

Nii ütleb taas rahvatarkus, kuid vihtlemisel võiks seda teadmist kasutada nii, et alustada vihtlemist jalgadest ja liikuda mööda keha pea poole. Nii on Veeroja sõnul vere ja energia liikumine kehas kõige parem.

Sauna ja tervise teemal rääkisid Tartu Ülikooli ajakirjandustudengid teadlaste ja asjatundjatega Vikerraadio saates “Huvitaja”. Soovitame kuulata ka reportaaži otse saunast ning saunameistri nõuandeid vihtlemise osas:

https://otse.err.ee/media/embed/931276

*Saunameister Priit Veeroja on etnoloogidelt uurinud sauna kohta käivat rahvapärimust, et kasutada neid teadmisi saunaprotseduuridel ja vihtade tegemisel.

Allikas: Novaator.ee/tervis

Toimetaja: Marju Himma

For Eda Veeroja, a sauna day begins early in the morning. The old smoke sauna at her home near Haanja in Southern Estonia takes up to 7 hours of heating before it’s ready to welcome guests. The sauna has no chimney, which means that the giant oven is being heated with big logs of wood until it reaches the maximum temperature, then the sauna is aired to let the smoke out. The accumulated heat will have to last for hours without lighting a new fire or adding wood.

It’s the end of May and the leafy hills of Haanja are covered in a hint of light green, not yet mature summer foliage. We arrive in the afternoon of a mild and sunny spring Saturday to experience a special treat – a spring sauna with white lilac blossoms. We had to make whisks of fresh young birch branches for everyone as homework. Going to the forest to collect branches helps to calm the busy minds of everyday worries, connect to nature and prepare for the awaiting rituals. As a group of girlfriends, we have been going to the Mooska smoke sauna annually for 8 years for a weekend retreat to cleanse the body and soul.

In 2023, the Estonian Rural Tourism Organisation is celebrating sauna culture in all its variety with dedicated educational and marketing campaigns and events. Sauna masters have been offering their services via a website. As a lucky coincidence, a documentary by Anna Hints – “Smoke Sauna Sisterhood”, was released in 2023 and has since shot to worldwide fame with the nomination as Estonia’s entry to the Oscars as the cherry on the cake.

So, with all that in background, we feel like we are hitting a trend. Eda encourages us to take a dip in the cool pond before entering the hot sauna to clear our heads. Then it begins. She leads her sauna guests through a 4-hour journey of chants and treatments, some of them reoccurring and familiar, some new and exciting. Eda has refined sauna rituals to a level of their own after she led the process of getting the Southern Estonian smoke sauna listed as a UNESCO intangible heritage in 2014. She leads the chants in her local Võro dialect to greet the sauna, to connect with ancestors, to deal with past pain and to open up for lightness and joy in the present. The huge oven of big stones gives off a mild but deep steam when Eda pours water (leil in Estonian, lõunõq in Võro dialect) over it. Rubbing salt and ash all over our bodies really gets the sweat going in the first rounds of the sauna. Off to the cooling pond, trying not to disturb the frogs.

More than 230 saunas have opened their doors to guests in 2023 – smoke saunas, wood-heated saunas, barrel saunas, raft saunas, tar saunas, peat saunas, igloo saunas, tent saunas, glass saunas, and the list goes on and on. Apart from those most private houses, cottages and many apartments have a sauna as well. And then there are dozens of public saunas, some of them quite legendary like the Kalma sauna in Tallinn’s Kalamaja district and the fancier spa saunas of course. There’s an abundance of saunas actually that Estonians usually enjoy weekly on Saturday evenings, to celebrate get- togethers and holidays. It’s not unusual to have a work meeting in a sauna.

Original articel is avalibe here: eas.ee

Haani loometare virtuaalne meediatuba kajastab lugusid lõunast ja mõtteid elust.

See on osake meie loomingulisest väljendusest, mis sündinud kaugtööna siin Haani mättal. Hoia end kohaliku eluga kursis siin: haani.ee

Mooska farm is a typical lifestyle farm in Southern Estonia. The powerful location at the foot of Vällamäe is amidst the beautiful nature and connects harmonically the farm life with the nature and the heritage of our ancestors. We, the Veeroja family, are proud to share our life with our guests and introduce local heritage, the pride of which is our traditional local food and the smoke sauna. The Smoke sauna tradition is inscribed to the UNESCO Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

The smoke sauna session in Mooska smoke sauna is customarily at least 3 hours of bathing enjoyment for the small group – family or friends (4-6 persons).

The smoke sauna session in Mooska smoke sauna is customarily at least 3 hours of bathing enjoyment for the small group – family or friends (4-6 persons).Body and soul will be cleansed while relaxing in a mysterious and comforting steam room, together with the host family, whisking, bathing, and pampering yourself with sauna honey. The rich aroma of burning wood is complemented by a whispered note of meat smoked in the sauna, a birch whisk (bunch of leafy twigs), and sauna honey. The sauna is located near a pond for a cooling swim when water is ice free or an invigorating dip in winter. During the experience your hosts will tell you all about and explain the Estonian smoke sauna traditions and beliefs. Smoke sauna is a holy (sacred) place for the family and alcohol is therefore not looked upon well neither before or during the sauna session.

Mooska farm has two smoke saunas for sauna sessions, each smoke sauna facilitates up to 8 – 12 persons, up to 25 persons. In case You have larger group, part of the group can go to

smoke sauna in the other farms in the same region nearby (facilitates also up to 10 persons).

The basic price for sauna session is 300€

Short walk in the farm introduces three smoke saunas of Mooska farm. Two of them are for the bathing, the third is for smoking the meat. Visitors get an overview of the construction, heating, sauna rituals and family traditions of smoke sauna. The most interesting part is to smell and see how the pork meat is smoked in the sauna. Duration of the farm visit is approximately 1,5 hours; basic price 10€ per person includes the degustation of the smoked pork meat.

Mooska farm visit with the introduction of the Old Võromaa Smoke intangible heritage and degustation of the smokes meat, has been awarded the EHE (Genuine and Interesting Estonia) quality label.

The fastest way to order a smoke sauna day is from the Internet link below. We will contact you by e-mail or phone before the sauna day to agree on the number of people and the start time of the sauna.

hotelwebsitebooking.com/mooska-suitsusaun/

We smoke and sell smoked meat that has been smoked traditionally in the smoke sauna 17€/kg

Basic price: 100€ per group per hour

loodusegakoos.ee

Contact us via e-mail info@mooska.eu

Warm visit is welcomed only by prebooking.

Eda Veeroja eda@mooska.eu

Find us on TripAdvisor

Facebook Mooska

Facebook Mooska Suitsusaunaliha (Mooska Smoked meat)

Mooska Ldt.

Mooska farm, Haanja parish, Võru county, Estonia 65601

info@mooska.eu

+372 5032341

A powerful documentary about the Baltic state’s sauna tradition has proved a surprise hit. But what’s it like for an outsider to join this sacred and intimate space?

“We are your sauna sisters now. Tell us what you’re afraid of.” The three women I have just met eye me expectantly. “Er, I wouldn’t say I’m afraid, exactly, more apprehensive about how hot the sauna will be, and how cold the water is …”

I’m at Mooska Farm in Võru county, south-east Estonia, to try a traditional smoke sauna. The earliest written records of Estonian saunas date from the 13th century, and the country’s smoke sauna culture was added to Unesco’s cultural heritage list in 2014 (many think of Finland as the home of sauna, but its sauna culture wasn’t listed until 2020.) This year, the smoke sauna has come to international prominence thanks to Smoke Sauna Sisterhood, an astonishing documentary that won a directing award at the Sundance festival and is Estonia’s entry for the Oscars.

The film appears to document the users of a single sauna over a year. In fact, filming took place at 10 saunas over seven years – and Mooska is one of them. It takes a little effort to reach it: I took a two-hour train ride from the capital, Tallinn, to Tartu, a university city and next year’s European capital of culture. There I met Elin, who is promoting Estonia’s “year of sauna”. We drove further south-east for an hour, then stopped in a forest to prepare physically and mentally. We collected drinking water from a spring, walked through a bog (Estonia’s most ancient landscape) and climbed the country’s highest hill, Vällamägi (a mighty 304 metres) for a few moments of mindfulness in a circle of trees.

Then it was onwards to Mooska, where I met Eda, the sauna master, and Kai, who would be helping. The four of us stripped naked and stepped outside. It was the last day of October, a few degrees above freezing, but with patches of snow on the ground. The swimming pond in front of me was frozen around the edges.

I had assumed we would warm up in the sauna before thinking about the pond, but no: we were going “swimming” first. “Don’t think about it, just do it!” commanded Eda. I took deep breaths and marched down the wooden steps into the icy depths, submerging myself to the neck for four breaths, then charged back up and straight into the sauna.

I lay on the top bench and instantly started to thaw out. I felt an incredible rush: elated and teary all at once. Eda closed the door and began to chant in her Võro dialect. The temperature rose as she threw water on the hot stones (to create steam – leil in Estonian) and started to beat a drum.

The sounds and sensations were otherworldly; part of me loved it, but another part wondered how long I could stand the raging heat. I had been told I could move to a lower level if I got too hot, and leave whenever I wanted, but a combination of self-consciousness and stubbornness kept me rooted to the spot.

Eventually, Eda said it was time to take a break. The sauna was in one half of a log cabin; the other room was pleasantly warmed by a central wood burner. We sat on rug-lined benches around the stove wrapped in blankets, drinking tea sweetened with honey. I learned what makes a smoke sauna unique: the wood in the oven is lit up to eight hours in advance; there is no chimney, so the room fills with smoke; the smoke is released before people enter, but the stones in the hearth remain hot.

We repeated the process several times over the next three hours: the ice-cold dip, the red-hot sauna, the tea and rest. Yet each sauna round was different: we rubbed ourselves with ash, then salt, and later honey, and washed it all away. We focused on our ancestors; on what we wanted to let go of and what we were thankful for; on times we had felt powerful. Eda instructed, chanted, rang bells, drummed, massaged our shoulders. At one point she told me to exhale like a coffee plunger, all the way down: “More, more, more!”

The climax of each sauna visit was the “whisking” with viht, dried bunches of leaves. Eda used them to lightly slap us all over, stimulating the skin and generating the most intense heat. Face-down in more of the leaves, I forced myself to breathe deeply, fighting a rising sense of panic. Finally, she encouraged us to let it all out by screaming. I sat up and managed a pathetic high-pitched shriek, while the others dropped to their knees and released deep, cathartic, guttural howls.

After my final plunge in the pond, I returned to the sauna and Kai told me to curl up “like a baby”. She tucked fragrant leaves around me and stroked them over my body. It was warm and dark and comforting, almost womb-like. I began to see why, in the film, the women tell such intimate, often traumatic, stories while they’re in the sauna. A sauna is a sacred space to Estonians – one where babies were once born, and the dead tended to – and, even to an outsider, it feels safe.

Afterwards we had dinner at Suur Muna, a cosy restaurant nearby where all ingredients are sourced from within 15km. It even serves traditional sauna-smoked pork, as seen in the film (these days it is smoked in a separate sauna). I find being in a sauna works up an appetite; I devoured my creamy chanterelles with purple potatoes, and sampled a sparkling rhubarb wine (divine) and a fermented birch juice (disgusting). I could barely keep my eyes open on the way back to Tartu and my room at Hotel Lydia, a 19th-century building in the old town.

There are about 400 smoke saunas in Estonia, mainly in the south-east, but they are not the only kind. There are 100,100 in total, for 1.3 million inhabitants, including Finnish saunas, electric saunas, raft saunas, barrel saunas and more.

For contrast, the next day I headed back to Tallinn’s hip seafront quarter of Noblessner, for an igloo sauna. This former submarine and shipbuilding district has been transformed over the past few years and now boasts Estonia’s only two-Michelin-starred restaurant, 180°, plus more casual dining (I had lunch at the excellent Lore Bistro), the Pohjala brewery taproom (complete with sauna!), the Kai Art Centre and lots of new apartments. It is also home to Iglupark, where groups can book a private igloo-shaped sauna (the Beckhams have one in their garden), with its own terrace and ladder down to the sea (from €50 an hour for up to 10 users, minimum three hours).

Most groups just hire the igloo, but I had my own sauna master, from Elamus Spa, the spa with the largest selection – 22 – of saunas in the Baltics. My session with Karl lasted about an hour, but still included many of the rituals – the scrubs, the musical instruments, the chanting, the whisking, even the yelling – and we finished with a plunge into the Baltic – and yes, it was. He also incorporated essential oils and shea butter, combining sauna and spa treatment.

It may not have had the intensity of Eda’s smoke sauna, but I still felt fantastic afterwards. Iglupark is more accessible for many, being close to the city centre and reasonably priced, and is one way of keeping the sauna tradition relevant to younger people. Even more affordable are the 41 remaining public saunas across the country, including six in Tallinn (about €6.50 for two hours).

I left Estonia wondering why Britain, another chilly northern European nation, doesn’t have its own sauna tradition. It may not get as cold as Estonia, but winter can be long, dark, wet and miserable. I learn that unheated Tooting Bec lido in south London has a sauna and is due to reopen after refurbishment. Bring it on! My sauna fear seems to have disappeared.

Perhaps I can ask Victoria Beckham if she wants to be my sauna sister …

The trip was provided by Visit Estonia. Guided saunas at Mooska Farm cost from €300 for three hours for up to eight people. Smoke Sauna Sisterhood is in selected cinemas now and will be available on demand from January

Loodusretk rahustab enne sauna meele ja hing saab üheks looduse ja looduga. Loodusretkel tuleb sauna kaasa mõnikord allikavett, taimi, vihtu ja helgem meel. Kõik rutud ja jutud (telefonid) tasub jätta auto juurde maha. Austame metsa rahu ja vaikust. Hingame hinge helgeks ja lubame mõtetel vaibuda. Loodusretkel räägime pisut Vällamäest pühakoha ja hiiena, meie esivanemate loodus tunnetusest ja loomulikult retkel nähtavast ja tunnetatavust. Retk on pooleteise-kahe tunnine jalutuskäik. Tähtis on, et jalatsid on mugavad ja ilma kõrge/terava kontsata. Liialt soojalt ei ole tarvis riietuda, sest Haanjamaa loodus loob paraja füüsilise koormuse. Mooska talus on koerad, seega lepime ette kokku koerte osalemise loodusretkel.

Jalgsi retk loodusesse alates 50€ grupp/tund või 10€* inimene/tund.

Talvel lume olemasolul lumeräätsa retk 12€ inimene/ tund.

Loodusretk rahustab enne sauna meele ja hing saab üheks looduse ja looduga. Loodusretkel tuleb sauna kaasa mõnikord allikavett, taimi, vihtu ja helgem meel. Kõik rutud ja jutud (telefonid) tasub jätta auto juurde maha. Austame metsa rahu ja vaikust. Hingame hinge helgeks ja lubame mõtetel vaibuda. Loodusretkel räägime pisut Vällamäest pühakoha ja hiiena, meie esivanemate loodus tunnetusest ja loomulikult retkel nähtavast ja tunnetatavust. Retk on pooleteise-kahe tunnine jalutuskäik. Tähtis on, et jalatsid on mugavad ja ilma kõrge/terava kontsata. Liialt soojalt ei ole tarvis riietuda, sest Haanjamaa loodus loob paraja füüsilise koormuse. Mooska talus on koerad, seega lepime ette kokku koerte osalemise loodusretkel.

Jalgsi retk loodusesse alates 50€ grupp/tund või 10€* inimene/tund.

Talvel lume olemasolul lumeräätsa retk 12€ inimene/ tund.